Sheila

“Sheila has dedicated her life to fostering, carrying on a family tradition that began with her mother in England. After immigrating to Australia in 1971, she and her husband fostered hundreds of children, a commitment now continued by her own daughter, preserving a legacy of care across generations.”.

Sheila has been a resident at Snug Village for just over 12 months. She grew up in England, where she and her husband lived until they adopted two children and decided to immigrate to Australia in 1971.

Fostering has always played an important part in Sheila’s life with her mother being a foster carer, and she followed in her footsteps. "My mum was a foster mum and when she got sick, I took home the baby that she had at that time.” She explains, “At the time you didn't have to have all these forms and rules and regulations. So, when that baby went, they asked me if I could take another one. And it just grew from there.”

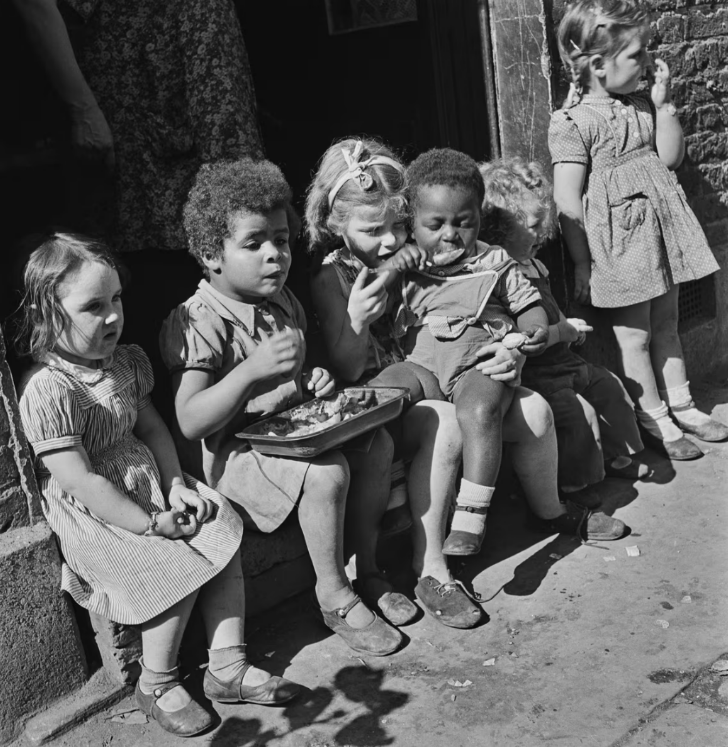

Sheila continued down this path, working as a private foster parent. In the UK private fostering was offered to West African families following the Ghanaian and Nigerian Independence in 1957 and 1960. Many African parents moved to the UK to study and worked to support themselves, Sheila and her husband would take in the children for several years until the parents completed their studies. “I had a Nigerian boy for four years, then his little brother came and then they took him back to Nigeria. I had them all the time and their parents would visit them occasionally.”

Sheila would return to work, “For a couple of years I worked as a machinist and embroiderest. I wasn’t there for very long it was when we first got married and before we moved into our own home. I used to make the badges that the army would wear on their caps.” During this time Sheila and her husband adopted two of their own children, “we adopted the children because I was told it would be very difficult for me to get pregnant. We felt we’d gone as far as we could in England and there would be far better chances for the children here in Australia.”

Although she was told it would be difficult to have children, she soon became pregnant after arriving in Australia, eventually becoming a mother of four. In Australia, Sheila found it challenging to find work without formal qualifications, so she returned to foster care. Over the years, Sheila and her husband fostered hundreds of children. Her husband was deeply involved also, serving as President of the Foster Carers Association where he worked with the community and government to support foster care initiatives.

Sheila particularly enjoyed caring for pre-adoption babies, though she acknowledges that adoption is much more uncommon now. Sometimes they fostered children with complex disabilities. She recalled a little girl who had to have extensive surgery due to being born without a fontanelle, which is the soft spots on a baby's skull where the bones that make up the skull are not yet joined together, “The top of her head was pressing against her brain, so we took her to Melbourne for surgery... She stayed with us until she was nearly two.”

Towards the end of her fostering many children were older, “Some of the older children were very challenging, especially in recent years with the conditions they had,” she says. “Sometimes we worked on family reconciliation, but it was rare. Usually, we had the children for short spans, except for our last foster son, who stayed until he was 18. It was usually a case of loving and leaving them.” Sometimes children came from challenging backgrounds, and she recalls, “One boy kept mooching around our gardens. We lived far out at Flowerpot then, and he kept looking around and said to my husband, "Where do you keep your stash?" My husband said, “I’ve got news for you mate, we don't have a stash!” But several of those children came up with that idea. And he was quite convinced that we were growing our own, but he couldn't find it."

Fostering children has become a tradition passed through female family members, Sheila’s daughter would step in to provide respite when she needed a rest and now her daughter is a foster carer, “she’s going through it herself with fostering twins—double trouble! I loved it, I loved the kids, and now my daughter is doing the same. So, we have a history of fostering from mum to daughter. During World War II, mum had to be responsible for the children on the estate, she made sure they were all accounted for, and she did a lot of work with them too.”

However, she says that fostering is much more difficult now. In Sheila’s time, foster carers formed a close-knit community, often providing respite for each other. However, she observes that this has changed, “My daughter tells me there’s no such thing as a respite carer anymore. You can’t get enough carers for the children they already have. People just don’t have the time. It’s a full-time job to be a foster carer, I wasn’t expected to work, and many women didn’t do that, we stayed home.”

For Sheila, fostering was more than a job; it was a life commitment. “It takes a village to raise a child,” she says.